In his book Chess for Zebras, Jonathan Rowson points the obvious, which as any deep truth is actually not that obvious at all. Knowledge and skill are two different things. To be a better player one need to improve skill. Rowson points out that training hard (going at the edge of one's comfort zone) is paramount. He repeats FM Ken Smith's advice that until 1800 level "your first name is tactics, your middle name is tactics, and your last name is tactics". He endorses Manuel de la Maza's book Rapid Chess Improvement. This tactics pursuit is subject of great following by a large number of players, and is often criticized by others. I think this uncomfortable truth goes for most of the chess publications. A book on openings could for instance be sold to one thousand 2000+ players, or seven thousand 1500+ players. Now the truth is that said book might improve the second category skill at the game by ... almost nothing.

Knowledge versus skill is found everywhere. For every craft (drawing, stock market trading, etc) most people amass knowledge and not skill. And I am not talking about football. I love playing, I like to follow news and results, but most people I play with have outstanding knowledge of the game (the follow teams and players very closely) great knowledge of how to play the game (dribbling, running, what TV shows them) but surprisingly low skill in understanding tactical and strategic aspects of the game. You would be surprised. Creating space, triangle passing, are often not understood by players who are very good dribbling and very good knowledge of history. Chess analogy would be a great knowledge of GM games, knowing who won the latest tournament, knowledge of opening lines 20 ply deep, but have not concept of the middle game plan that these opening are leading to.

Increasing skill is the most interesting thing. There is nothing like winning games against increasingly skilled opponents. Skill is the fundamental aspects of flow, where one must match a difficult challenge against with a good skills. This is why I enjoy a large variety of board games beside chess: I thoroughly enjoy learning new games, discovering tactics and strategy anew. Will I ever be a great expert at any of them ? likely not. My own way of gaming is the one of diversity (with a love for chess).

Enjoy the journey of playing games,

Sunday, 29 January 2012

Better calculation: from trees to stones to ...

Basic calculations are the bread an butter of chess games. Imagining the different possibilities is one of the main activities when playing chess. Now, how should one do that ? Does everyone do it the same way ? Is there a correct and an incorrect way to do it ? How many move ahead should one think and how to improve calculation depth ? Don't get your hopes too high, I'm not listing these questions because I know how to answer them, but I genuinely would like some input from everyone. Getting the question right is quite often in life the most important thing. As far as I understand for practical play, the following are the utmost importance for tactical play:

I am a bit surprised that you have an overwhelming supply of pattern recognition material but much less on calculation. You are somehow supposed to just get better at it as you progress along. There are, however, a couple of books that are helpful

Now if one wants to think about better move selection it is a broader topic than the calculation. There again there is a large supply of strategic level material. In Jeremy Silman's books, he deconstructs the thought process of lower ranked players and introduce a structured way of thinking about the position, by listing the imbalances. This sure is important, as he points out how players tend to calculate straight away without thinking strategically in the first place. Methods of move selection are important, but I would like more input on the calculation process for the time being.

Kotov's method is intuitive. Consider candidate moves, and work your way through all the variations branch by branch

This has been criticized by many authors (see John Nunn's Secrets of Practical Chess in which the first chapter is devoted to discussing the drawbacks and improving the Calculation process), but the practical calculation advice being so sparse Kotov's methods are quite often discussed as the test bed of the calculation though process.

Jonathan Tisdall, a Norvegian GM of American origin, have interesting book of the thinking process. In the first chapter he discusses the shortcomings of the tree methods, and underlines the role of intuition and also inner dialogue. The second chapter is a description of his method of calculation. It is actually quite simple to summarize. It relies on board visualization, and henceforth blindfold chess training is very central to the process. The idea is the one of a stepping stone: one should visualize very clearly a position, from which the dynamic calculation is performed. Once the position loses clarity, one should then reset its mind on visualizing that troubling position, and then go ahead on calculating further. Given that one only has one position from which to calculate at a given time, it is theoretically possible to calculate in the way to great depth, stepping from position to position. The simplest example of the technique is the following: imagine the strating position, then without looking at a board play the following moves in your head 1. e4 Nf6 2. Nc3 d5 3. e5 d4 4. Nce2 Ne4 5. c3 dxc3. Now bring this position as the forefront of your mind and whink about white's move.

Tisdall goes on talking about how players visualize the board, citing a nineteenth century study by Binet.

Vision, the though process of the chess player, have been analyzed in great depth by Scottish GM Jonathan Rowson in his books The Seven Deadly Chess Sins and Chess for Zebras. There are too many interesting things to summarize here, and most of the material goes far above my head, but he does say that the strongest players have a very abstract view of the board. Think that it is a lot easier to think and memorize familiar chunks of information. I can imagine the castled king position with the knight on f3 as being one bit of information, not as six pieces and pawns on the board.

All this being said, what should I do now to get better ?

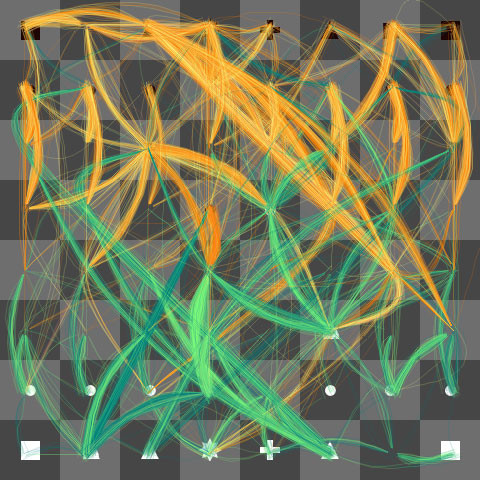

Just to finish on a cool image: pruning out the tree in an efficient way also turns out (by chance) to be the way current chess computer thinks. Just for fun this image on a visualization of the variations form Thinking Machine 4

gl, hf

- basic board visualization/awareness. By this I mean seeing the squares an outpost knight could go to. If one does not sees this or has to 'calculate' the one move squares of the knight, it is a lot more difficult to pay attention to basic forks, etc.

- Pattern/motif recognition. There is no calculation per se involved into recognizing a pin. A part of tactical play is built on this immediate recognition

- Calculation of variations. This is the 'what if'.

I am a bit surprised that you have an overwhelming supply of pattern recognition material but much less on calculation. You are somehow supposed to just get better at it as you progress along. There are, however, a couple of books that are helpful

- Thinking like a Grandmaster, Alexander Kotov.

- Improve you chess, Jonathan Tisdall

Now if one wants to think about better move selection it is a broader topic than the calculation. There again there is a large supply of strategic level material. In Jeremy Silman's books, he deconstructs the thought process of lower ranked players and introduce a structured way of thinking about the position, by listing the imbalances. This sure is important, as he points out how players tend to calculate straight away without thinking strategically in the first place. Methods of move selection are important, but I would like more input on the calculation process for the time being.

Kotov's method is intuitive. Consider candidate moves, and work your way through all the variations branch by branch

This has been criticized by many authors (see John Nunn's Secrets of Practical Chess in which the first chapter is devoted to discussing the drawbacks and improving the Calculation process), but the practical calculation advice being so sparse Kotov's methods are quite often discussed as the test bed of the calculation though process.

Jonathan Tisdall, a Norvegian GM of American origin, have interesting book of the thinking process. In the first chapter he discusses the shortcomings of the tree methods, and underlines the role of intuition and also inner dialogue. The second chapter is a description of his method of calculation. It is actually quite simple to summarize. It relies on board visualization, and henceforth blindfold chess training is very central to the process. The idea is the one of a stepping stone: one should visualize very clearly a position, from which the dynamic calculation is performed. Once the position loses clarity, one should then reset its mind on visualizing that troubling position, and then go ahead on calculating further. Given that one only has one position from which to calculate at a given time, it is theoretically possible to calculate in the way to great depth, stepping from position to position. The simplest example of the technique is the following: imagine the strating position, then without looking at a board play the following moves in your head 1. e4 Nf6 2. Nc3 d5 3. e5 d4 4. Nce2 Ne4 5. c3 dxc3. Now bring this position as the forefront of your mind and whink about white's move.

Tisdall goes on talking about how players visualize the board, citing a nineteenth century study by Binet.

Vision, the though process of the chess player, have been analyzed in great depth by Scottish GM Jonathan Rowson in his books The Seven Deadly Chess Sins and Chess for Zebras. There are too many interesting things to summarize here, and most of the material goes far above my head, but he does say that the strongest players have a very abstract view of the board. Think that it is a lot easier to think and memorize familiar chunks of information. I can imagine the castled king position with the knight on f3 as being one bit of information, not as six pieces and pawns on the board.

All this being said, what should I do now to get better ?

- Go back to my Palliser book and do tactics until my forefront sweat blood

- Same but I consciously think about the way I calculate

- Should I study some miniatures blindfold. Is this wort it ? (disclaimer: I have very poor blindfold skills. I can see some stuff, but it;s as if the diagonals are wiggly and do not quite connect. It requires me an amazing effort to see the influence of bishop in blindfold way. Maybe I should train on that).

Just to finish on a cool image: pruning out the tree in an efficient way also turns out (by chance) to be the way current chess computer thinks. Just for fun this image on a visualization of the variations form Thinking Machine 4

gl, hf

Sunday, 22 January 2012

Kasparov-Short: tactical variation

I am working my way through the 1994 game between Garry Kasparov and Nigel Short, rading Nunn's analysis. I think it is worthwhile to post a few tactical pattern separately, So I can then post my own understanding of the game with a clear focus on the strategy. Of course Kasparov did not play 7. Be2 but the following explain why he did not :

I will post more things about this game later on.

I will post more things about this game later on.

Tuesday, 10 January 2012

Kramnik's tactical brilliance

Enjoy the following combination taken from John Nunn's "Learn Chess Tactics". White to move and win decisive material. This is not straightforward and requires some calculation.

Nice application of fork-decoy-pin-fork !

Nice application of fork-decoy-pin-fork !

Saturday, 7 January 2012

The strategy of Twilight Struggle

Twilight Struggle is one of the most highly ranked board games. I have only played a few games but it is starting to grow on me and the tactical and strategic patterns start to emerge. The game (like all awesome, deep games) has a very steep learning curve: is is necessary to get acquainted with the cards. This comes naturally after a few plays. I have to mention the brilliant and original blog twilightstrategy.com that greatly helped me flatten the learning curve. The post on the opening, Events vs. Operation, and the reshuffles are must read for beginners. Keep up the good work

Learning tactics from several sources: worthy books

Learning tactics from books (or online, or as ebooks) is my bread and butter for improvement. Usually the books are either a collection of positions or an exposition of the different tactical patterns. I find both approaches are mandatory and complementary. Tactics is not just the fact of 'trying out' to calculate variations by brute force (Silman talks about how beginner insist on considering moves before analyzing position) but the fact of recognizing the patterns in the position (e.g. where is the key weakness in the position, and then calculating the tactics itself. It took me a while to understand this and it made my tactical awareness greatly improve. What are the loose pieces ? The pins ? The overloaded pieces ? This two prong study might converge to a one prong once the basic motives are understood and set in stone, only 'blind' tactics can be used to stay sharp.

the book I really like and use a lot are:

I complement this with the study of How to Beat Your Dad at Chess, Murray Chandler. This book is a one of a kind in the sense that it cover the basic mating nets. Despite the goofy title it is an extremely useful book and well worth it for beginner/intermediates. There is two more books in the same format and collection, one on tactics and one on openings, and they are good books though I have had no time for studying these.

the book I really like and use a lot are:

- For the pattern by pattern exercises: Chess Tactics for champions, Susan Polgar. The exercises are from 'made up' position and are reasonably simple, I find this was a great beginner book and I recommend it.

- For the set of positions: The Complete Chess workout by Richard Palliser. Position are from tournament games, alphabetically ordered by tournament name. You never know what is thrown at you, the position are realistic, and the gain are not necessary checkmate but often just the gain of a pawn. I also thoroughly recommend this book.

I complement this with the study of How to Beat Your Dad at Chess, Murray Chandler. This book is a one of a kind in the sense that it cover the basic mating nets. Despite the goofy title it is an extremely useful book and well worth it for beginner/intermediates. There is two more books in the same format and collection, one on tactics and one on openings, and they are good books though I have had no time for studying these.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)